Globalization Architecture

Our dwellings began as rugged practical things. What materials could stand side by side holding up another material that would cover us from rain and sunlight. The more we went beyond subsistence the more time we stayed in these shelters, and soon they became something beyond just that. The details with which we would adorn our shelters quickly became part of the identity of the peoples that saw it as an expression of who they were. To look at a structure was to see a cultural brand. It was not just an expression of what these people were but also what they strove to be. The great Catholic cathedrals with their massive domes and grand entryways reminded the individual of the power that was beyond oneself. The rows of columns that would hold up an ornate pediment with carvings of ancient legends seemed to symbolize the collective strength of mediteranean democracy. The imperial grandeur of the many monarchically named styles of British architecture reflect the era and presence of the sovereign. Up to a point this was the understood function of architecture beyond the practical: to symbolize a people.

The point when that changed coincides with a change in the fundamental way in which Western peoples were to think. After the apex of European nationalism in the 30s and 40s, the Allied Powers set to rebuild upon the fertile ashes of the Second World War. The defeated foe of fascism was placed as the furthest post of immorality, before which all morality would be based. As far from the tenants of this dark ideology as one could go would be the measure of moral worth. The ideology of fascism became the secular devil. Instead of the hyper nationalism that permeated fascist governments and its culture, the West would now do the opposite. The world would take on a more collaborative stance. The momentum of international relations would be in tying tighter the unions of the world, spurred by trade. With these unions came the question of culture. These supranational bodies would not use Western culture to influence their brands, for it would not reflect the global level from which many disparate cultures were operating. A new style would have to be adopted. A style that would be congenial to every culture in the world. The ornate and revivalist buildings of the past quickly lost their appeal. Shining glass and stone monoliths rose from the earth to dwarf these old symbols. A time traveler from before the post WWII era would be stupefied by the imposing, faceless elementary shapes that became the seats of modern supreme power.

UN Headquarters, New York, New York

International Monetary Fund Headquarters, Washington, D.C.

World Bank Group Headquarters, Washington, D.C.

It is not only governmental buildings that have presented themselves in this way. The other major institutions of power, the corporations and universities have likewise adopted this style in droves. The corporate buildings have become iconic because they are all densely arranged, creating a visually unified display of power. The skyscrapers exude financial power which is exchanged for pure power. Just by the name alone can you feel it. Alas, the ornate details of these giants have faded into nondescript sheen. The universities are a more disappointing case. It almost seems natural that corporations will become huge pragmatic towers. But the university setting is a more thoughtful, sacred place where the buildings were meant to illicit feelings of inspiration, mastery, and of the past. Many of the old university buildings look like churches or mansions of nobility. It is no wonder why Jefferson chose to replace the usual central church with his Rotunda library to show “the authority of nature and power of reason,” compared with the traditional authroity of nature and power of God. I still think there’s a reason universities keep their oldest, and most beautiful, buildings as the centerpiece of the campus. Maybe they agree in a way. The parallels between religious and pre-globalized academic architecture are undeniable. It showed the reverence for the pursuit of scholarly knowledge like the pursuit of salvation.

Though not any longer. Every new campus building conforms to our new global architecture. The university settings resemble industrial buildings. Pragmatic and soulless warehouses of people made to produce a worker like an assembly line produces doorknobs. Students are now more like customers seeking better financial prospects from the sign-off of an institution that one has indeed sat through the half-baked ramblings of an academic salesman. Only those of extreme wealth or those of the International-Student Class, those of children of foreign aristocracies, can hope to emerge again. This is why the Diversity and Inclusion business model exists. Not to gather diverse perspectives, which is obviously not the case on campuses, but to gather diverse streams of income to fatten the university administration, which now outnumber full-time faculty. It’s clear to see the motivation of the modern university is profit as much as any business, if not more. It directs the hiring of the faculty, admissions of the students, curricula of classes, and is most accurately portrayed in the warehouses in which they deposit the doe-eyed youth awaiting the droning rotor to send them into the grinder to extract their financial worth. But this is a digression, and the exact causes and evolution of this university business model are unknown to me. Though the cause of a fire is not what makes it dangerous.

Like the rows of concrete city blocks of the Soviet Union, the more control a power has over its people’s lives, the less individualistic buildings begin to look. Historical authoritarian architecture and out new, globalist architecture have a worrying resemblance. Could it be that the central planning of authoritarianism and the planning of large businesses have similarities? In a way, corporations are themselves authoritarian. The Chairman and his advisors make the final decision. This is not to say all business will have an authoritarian effect on architecture. It is the level of wealth concentration in business that mimics the power concentration in authoritarians. Money is power. There may be more here, but I feel like that would veer away from the subject of architecture.

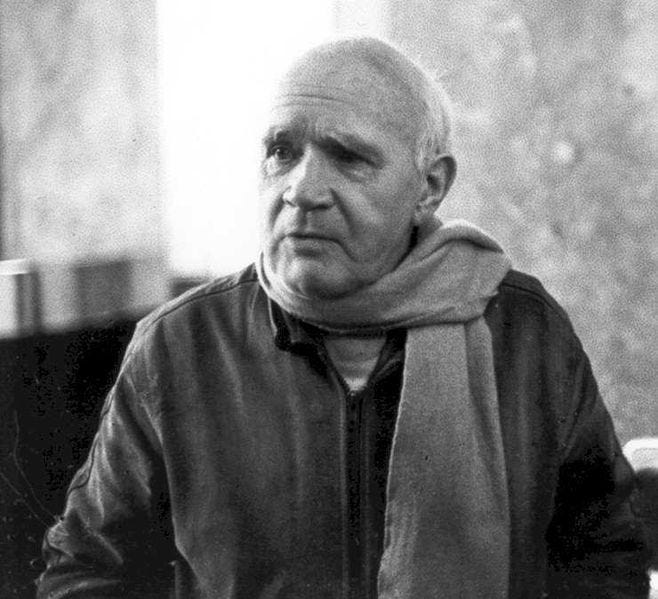

Mark Zuckerberg’s sense of style somehow seems to match modern architecture. Trying to be universally relatable, while being a totally sterile .

You may think that being critical of architecture is the last on the list of important things. I suppose, in the grand scheme, the little wobbly structures we erect all crumble and nature takes her rightful place once again. But it really bums me out thinking of the reasons things look ugly and oppressive. The way our societies look is directly tied to how our societies are. Without this realization we ignore messages prior societies are telling us, and forgetting that we are telling futures societies about ourselves.